Democrat September-October 2008

Roots of democracy

The Chartists

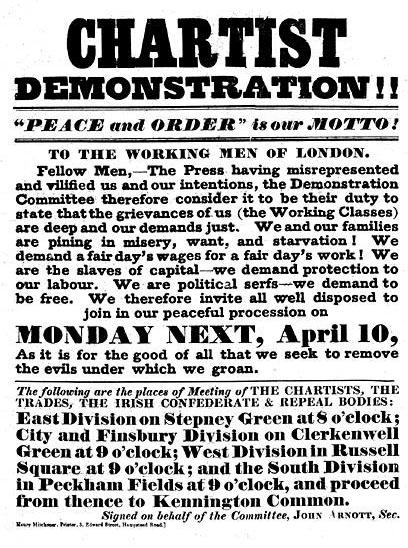

In 1836 a committee of six MPs and six working men including William Lovett from the London Working Men’s Association, drew up a petition to Parliament containing six objectives:

• Suffrage for all men 21 and over

• Equal sized electoral districts

• Voting by secret ballot

• An end to the property qualification for parliament

• Pay for MPs

• An annual election of parliament

These objectives acted as a catalyst to unite many organisations around Britain including trade unions. It was taken up by hundreds of thousands of industrial workers because they saw an answer to their intolerable economic grievances.

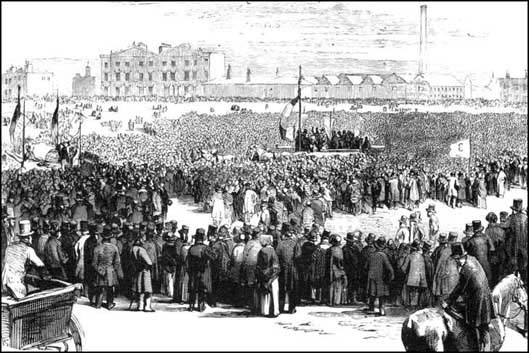

Chartist meeting - Kennington 1848

In 1838 the six points were formed into a Parliamentary Bill which became the actual People’s Charter. This was endorsed at mass rallies all over Britain including 200,000 in Glasgow, 250,000 in Leeds, 300,000 in Manchester and 80,000 in Newcastle.

Strategy and tactics were formulated to gain acceptance of the Charter. These included a campaign of demonstrations, a mass petition and national Convention (the name deliberately linked with the epoch-making French Revolution). If the petition was rejected by Parliament there would be a general strike or ‘sacred month’.

The movement spread and changed character with three strands. There was the right wing who wanted to use peaceful persuasion and education. The centre was grouped around Feargus O’Connor supported by industrial workers, miners and the ruined hand workers of the North. The left wing was led by O’Brien a socialist and Owenite who developed an analysis of Britain including the role of the law, new police force and army.

The Chartist petition was signed by one and a quarter million people including many women even though the Charter did not demand suffrage for them. This petition was presented to parliament in 1839, but, MPs voted 235 votes to 46 not to hear the petitioners.

The employers and ruling class were frightened the Charter would overthrow the English Constitution. Historically this marked the point where workers recognised they were an independent force and their opponents included the industrial employers.

The Chartist Convention faced by the rejection discussed “ulterior measures” which included direct action and a general strike. But, there was no organisation in place to call a strike.

Later in 1839, and still shrouded in mystery, is the Newport rebellion. Three columns of Chartists, mainly miners from Wales, marched on Newport under cover of night to demand the release of a Chartist leader. Hastily sworn in Special Constables arrested Chartist leaders. Even though plans were kept secret, soldiers waited in hiding and shot at the columns killing ten people.

The leaders were put on trial for conspiracy and sentenced to death. The sentence was commuted to transportation to Australia. [Following a special petition an unconditional pardon was granted in 1855.]

Over the next months many Chartist leaders were arrested and imprisoned causing the movement to go underground. A revival did take place as these leaders left gaol and the National Chartist Association was formed. Even though illegal this was in practise the first national political party and comparable to those of today.

A second petition with three and a half million signatures was presented to, and again rejected by, parliament in 1842. As before, the NCA dithered over what action to take.

This coincided with a depression which lasted a year where there was short-time working, wage reductions and rising food prices. Workers took things into their own hands and in Lancashire, the Midlands, Scotland and Yorkshire they went on strike and made economic demands.

The unrest became widespread and known as the Plug Plot because plugs in steam boilers were removed to prevent factories working. The NCA eventually recognised the strike and a Manchester trade union conference demanded the Charter be implemented.

A weakness of the Chartist movement was failing to forge strong links with the trade unions and workers. However trade unions did learn from this period that the detail of organisation must be carried out to gain changes and to conduct a class struggle. Unions became a regular part of workers lives.

All the objectives of the Charter except the annual parliament were eventually attained.

Today there are obvious parallels with the situation the Chartists faced from which lessons can be learnt and avoided over the all important question of democracy in all forms.

Roots of Our Rights I and II contain a series in similar vein of historical pieces in pamphlet form and now available for £2.40 the pair post free.